“We will resolutely support the Chinese economy and markets, and do our absolute best in preventing foreign interference from influencing our local politics”, bellowed Xi Jinping.

The Chinese government has been on a roll in 2023, introducing a slew of economic measures to support the Chinese economy. They include:

- Reduction in interest rate and mortgage rates

- Measures to increase household spending through tax relief

- Increasing construction spending

- ‘Liberalizing’ the market access for private firms

- Approved more sovereign bond issuance

But how effective are they? And are they actually stimulating consumer spending and business investments?

Here’s where the Chinese government keeps well-guarded secrets to the everyday people. Let’s uncover the hidden secrets to China’s ‘policy supports’ that the government doesn’t want you to know about.

The Monetary Policy or Interest Rate Policy is Kind Of Broken

This could be a game-breaking bug in gaming terms. You see, the interest rates with an S are kind of broken and have been so for a long time.

Typically, a central bank will reduce interest rates to stimulate consumer spending and business investments when the economy is not doing well, and vice versa. Because of this, the stock markets will typically trend downwards and upwards depending on the impact of interest rates on the economy.

Have you ever wondered why China has like 4 interest rates that they control? Here, let me list them all down here.

- Reverse Repo: Short-term open market operation rate

- Medium-term Lending Facility: Central bank lending to market for the medium-term

- Loan Prime: Average interest rate for loans provided by banks to customers

- Reserve Requirement Ratio: Minimum reserves banks need to keep with the central bank

Why would they even need that many if one interest rate can do it all? The reason is simple. Monetary policy in China seems to be not that effective with one interest rate. Hence, they introduced a bunch of them.

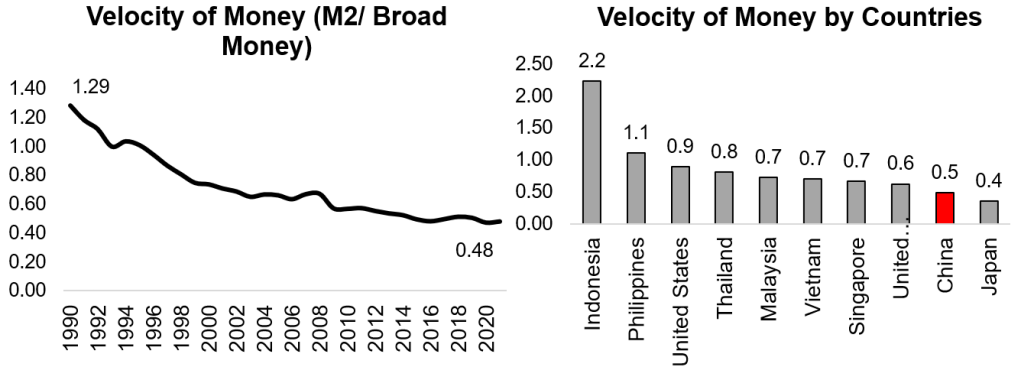

In my opinion, money velocity is a good way (but not perfect) to gauge the effectiveness of the monetary policy. It determines how fast or slow people are spending cash in the economy.

The velocity of money in China is very low at 0.48 compared to other economies around the world. It has been steadily declining since 1990 and is at its lowest point now.

Here’s the way to interpret this for a layman. China needs RMB0.48 for every RMB1 of nominal gross domestic product in 2021.

Isn’t it any wonder that monetary policy is not effective if you need to increase the money supply so much more to increase economic growth?

Here’s what the experts in the field say about monetary policy in China:

- IMF: Our results suggest some progress but also continued difficulties in the transmission of monetary policy.

- Chen et al (2017): The monetary policy transmission through bank lending channels becomes less effective in China.

- Huan, Ni, Xu, Zhan (2021): The role of the neoclassical interest rate channel in the overall effect of monetary policy is still relatively low (31%).

Government Spending and ‘Confidence’ Doesn’t Seem to Work Well Either

I have a ratio that I always fall back to when I want to look at whether a country’s fiscal policy is effective or not. It is called the fiscal multiplier. The best way I can explain this is how much gross domestic product is added for each dollar spent by the government.

Hence, the lower it is, the worse a fiscal policy transmission is and vice versa.

In China’s case, the IMF categorized the country as ‘low’, which means that its government spending transmission to the economy is not that great.

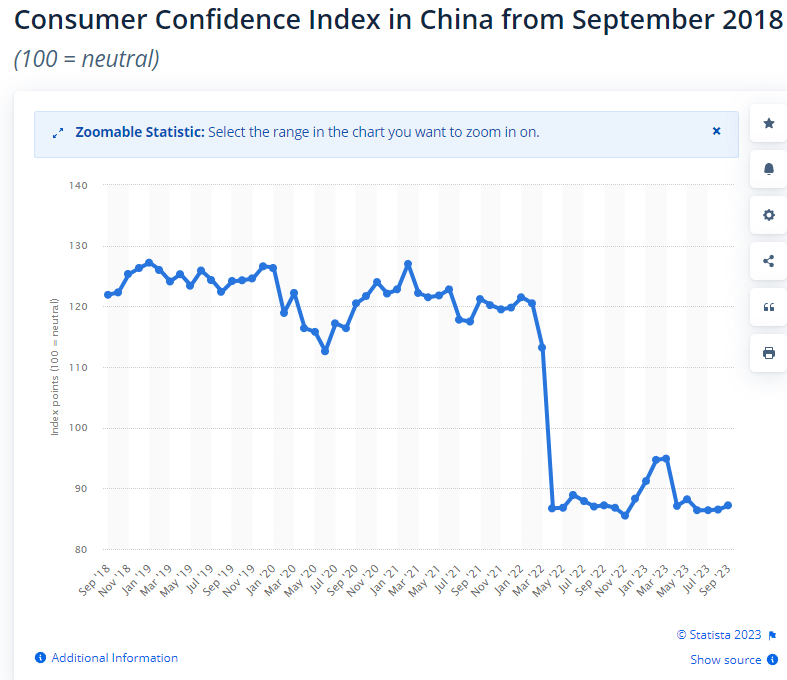

You see, this year has been a hard one for China. What was supposed to become the coming of a bountiful year for the country, turned out to be outright disappointing.

China tried to boost sentiments on the ground by promising to ‘wholly’ support everyone by giving people handouts and spending more on the construction sector.

But that hasn’t panned out. The consumer confidence index is down from its peak of 94.9 in March 2023 to 87.2 in September 2023.

While the Chinese government projects that economic growth will come up to ‘about 5.0%’, this is certainly a far cry from the 5.5% to 6.0% growth that the market expected in early 2023.

And here is where the story gets more interesting.

You see, Chinese consumers have actually fallen back to saving instead of spending despite all the talks from the government to boost consumer spending.

Furthermore, the Chinese government does not want you to know about how effective its ‘government investments’ are. If you did, you would probably be saying ‘Just why are you dumping that much money into things that don’t work?’

China is Hiding a Dark Past to Why Its Consumers Are Still Dead Set on Saving

China wants its consumers to spend, but they are not. Instead, they are saving.

Data from Morning Consult shows that Chinese adults increased their savings in 2023 from an already high number in 2022 and that for every RMB1 earned, RMB0.27 is tucked away for savings.

The news always talks about how Asians just have a tendency to save and that their culture is different from Western mindsets of spending.

I think this is just so superficial and lazy journalism. There is a much darker past here that few talk about.

In the 1980s and 1990s, when China was in full boom with the economy being opened up and liberalised, an odd thing occurred in the countryside.

Troves of migrants left the countryside and flooded into the cities where the government promised jobs and salaries. After all, the country was just recovering from the massive famine caused in the 1960s and 1970s by Mao’s disastrous policies.

The thing is they promised jobs but not social goods like education, healthcare and housing. China operates a Hukou system which effectively means that he or she is eligible for social services like education, housing and healthcare in a particular province and area. And that system extends to status between urban and rural areas.

This basically means that you will not be eligible for these social goods and services in another area that you are not registered under.

If you have a child or elderly, you can’t bring them to the areas that you are working in where you don’t have a hukou registration. And if you want to register a new hukou in a new area, you have to relinquish your previous one.

Typically, governments or municipalities make it very hard for you to change your Hukou.

Hence, in major cities in China, you have these huge ‘migrant’ populations that work low-paying jobs even today. And they don’t have access to these social services.

For them, they have to pay out-of-pocket for a lot of things and they send a huge portion of their income back home to their children and parents.

Furthermore, let’s talk about houses in China. They are just so god-damn expensive. House price-to-household income ratio is at 30 times – freaking 30 times. Most advanced economies are below 10 times.

For you to own a house, you have to plunge almost every penny into the downpayment and even then, you are stuck paying an exorbitant amount of interest on your loan to even afford it.

I know, the property sector has been in a rut the past year but owning a home in China is still a pipe dream for many but they still save up for one.

You would think that’s the whole story but the past gets even darker for investments.

Investments are Not That Efficient and Effective

Oh boy, let’s rip into China’s investments.

I think this is something that not many people know about. Most of the investments in China even from the 1980s, are plain dogshit. It doesn’t matter whether it’s government or private investments.

And this is tied very closely to credit and funding – aka the banking sector.

Have you heard of zombie financing? If you haven’t, you can try googling it for Japan. Japan popularized this term in the 1970s and 1980s, the Ministry of Finance and Bank of Japan basically told the banks which sectors to lend to.

That resulted in a lot of these loans being ‘zombified’ as they were channelled to non-productive use and didn’t generate many profits back.

The same thing happened in China in the 1980s and is still happening now. I like to use this term to describe this – a big Ponzi scheme run by the Chinese government. And that Ponzi scheme has continued until today.

Frank Dikotter explains it well in his book China after Mao. Most of the state-owned enterprises in China are essentially zombie companies, where the ‘owners’ just put on a front and say they are doing business and hire a lot of workers.

But in essence, they just produce things where the demand is not there. These workers get paid, and the owners siphon whatever funds that were provided by the government.

However, because most of these products don’t have demand, they are normally sold below cost and the state-owned enterprises suffer big losses.

The government has to bail out these state-owned enterprises as they employ a lot of people, often by directing banks to lend more to them.

And the cycle repeats again and again.

Furthermore, the Chinese government loves and I mean LOVES, channelling funds and credit to the infrastructure, construction and property sectors.

They score very easy political points with the Chinese masses as they can just go ‘Hey, look, we build these roads and houses for you’.

However, it has led to overbuilding in the country with no fundamental demand supporting these constructions.

Even many institutions and academicians have highlighted these issues – although they are subtle when doing it.

- IMF: “Lack of resource allocation to more productive firms was associated with slower manufacturing total factor productivity growth. Allocation of a larger share of credit and investment to infrastructure and housing led to lower returns to capital.”

- Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: “China is investing too much in unproductive projects and consuming too little. Decades of massive infrastructure and real estate investments have exhausted the backlog of high-productivity projects and are now dragging down the economy.”

- Paul Armstrong-Taylor: “Most high-return investments have been completed, and current investment returns are lower. The purpose of investment (for the Chinese officials) is not to earn profits but to hit GDP targets. The productivity of investment does not matter.”

And there is a bigger issue here that I learned from the Carnegie paper linked above. China actually capitalized its investments when they were supposed to be written down or expensed.

For the layman out there, if you lose money on your investments or assets, you are supposed to declare that you made a loss on this when all signs point to one.

China just says, “Well, it isn’t a loss if we don’t acknowledge it” and keeps these assets at their original value.

Holy shit, what the heck?

This just means that these companies who were supposed to be making big losses are not on paper, making losses. Man, talk about investments not being productive.

Conclusion

Whew, that was a long article. However, I am glad I actually put a lot of effort into this as I feel that this topic of China’s policy support is not really known outside of academia.

If you are an investor in the Chinese markets or are just interested in the background behind China’s policy-making, I hope this really helps you out in your decision-making and knowledge-gathering.

I really had a lot of fun, writing this.